I hear a series of sharp shrieks behind me before I’m unceremoniously shoved forward by a small surge of tourists rushing out onto the deck of the Taktsang Cafeteria. Annoyed, I retaliate by jostling the woman next to me, my elbow primarily making contact with the plush down of her black Patagonia parka, before looking up and seeing the cause of the commotion. The mist shrouding the mountain has begun to clear, leaving us with a picture-perfect view of the Tiger’s Nest Monastery (also known as Paro Taktsang). It’s just like on Instagram, but, well…reality. On cue, a cross continental chorus of superlatives ensues, harmonising with the unceasing clicking of shutters.

As we recommence our ascent—the fortress-like structure perched impossibly on the cliff face now flitting in and out of sight—I vainly attempt to mask the fact that I’m huffing and puffing enough to blow down one of the three little piglets’ houses by asking my guide Sangay how many people usually do this hike a week. There’s less now because it’s monsoon season, he says, though there can be hundreds a day in the high season. “But it’s not just a hike, you know,” he adds after a beat. “For locals, it’s a spiritual pilgrimage.”

Somewhat chastened, I fall silent. Certainly, for locals—many of whom joined us, being a Sunday—the journey to Tiger’s Nest Monastery was not merely a way to counteract the calories from the previous night’s multicourse meal, but an important part of spiritual wellbeing.

Since Bhutan opened up its borders to tourism just over half a century ago in 1974, the country has curtailed overtourism by adopting a “high value, low volume” model, targeting well-heeled travellers by cultivating an air of exclusivity, implementing a daily sustainable development fee (SDF), and requiring visitors to be accompanied by a local guide outside the cities of Paro and Thimphu. The $100USD daily SDF (down from $200USD in 2023) is valid until 2027 and applies to all tourists, with the exception of Indian nationals, who pay ₹1200INR per day.

Those who do make it to the Himalayan kingdom do so for multivarious reasons: many out of curiosity about the road less trod, some for spiritual guidance, perhaps a few to burn off calories in surroundings more aesthetically pleasing than the local Virgin Active, and others in pursuit of enlightenment in the last Shangri-La.

Indeed, the fictional utopia in Lost Horizon, British author James Hilton’s 1933 novel, is often cited in reference to Bhutan. Not merely for its lush natural beauty and remote—and somewhat inaccessible—location in the Himalayas, but for its agrarian values, commitment to cultural preservation, and protection from external influences.

Equally adduced is the concept of Gross National Happiness (GNH), a practical development framework introduced by the fourth king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, which underpins the nation’s lawmaking and places an emphasis on national contentment over economic markers. Despite what the catchy name—and some of the tourism department’s marketing imagery—might suggest, Gross National Happiness isn’t measured by smiles and giggles, rather the overall wellbeing of the nation in relation to both its human inhabitants and the land itself. The framework has underscored the implementation of free universal healthcare (helped, in part, by the country’s SDF for tourists) and policies banning the sale of tobacco products and plastic bags, as well as laws mandating that a minimum of 60% of the country remain under forest cover (that figure currently sits at over 70%) and implementing mandatory guidelines for new construction to protect the country’s traditional architecture.

When you have the destination in mind, it makes the journey harder…

Inside the Tiger’s Nest Monastery, Sangay tells me that it’s actually the tigress’ nest; a reference to the feline that Guru Rinpoche, the founder of Vajrayana Buddhism, rode to the precipitous site. Oh, and the tigress was also the guru’s consort in disguise. As he continues to paint a colourful tale involving celestial beings and the banishment of evil spirits, I attempt to commit the ornate golden interiors to mind (photos are prohibited inside) and begin to feel lightheaded. Briefly concerned about the presence of evil spirits, Sangay assures me it’s more likely the altitude at play here, with the Paro Taktsang sitting over 3000 metres above sea level.

Back on the ground, the mist has completely dissipated and we have a clear view of the taktsang from the carpark. The 17th-century building looks like it was dreamt up by M.C. Escher and clearly executed by a construction team with little regard for the constraints of gravity. Legend says the building was anchored to the cliff face by the hair of female celestial beings known as khandroma, which honestly seems as plausible an explanation as any.

“It’s a good thing we didn’t see it earlier,” Sangay tells me. “When you have the destination in mind, it makes the journey harder.” For most travellers, the hike—nay, spiritual pilgrimage—to Tiger’s Nest Monastery acts as the denouement of a trip to the Himalayan kingdom; a reward for taking the path less travelled. For me, it’s just the beginning.

“You must be jetlagged,” my server had said sympathetically over dinner the night before, as she arranged a medley of vegetable curries, the ubiquitous ema datshi—the national dish of Bhutan; a spicy concoction made from green chillies and cheese—and a heaping bowl of red rice in front of me. It was nearing midnight and I’d just arrived at Amankora Paro, one of a quintet of luxury lodges by the Aman group strewn across the kingdom. I nodded wearily, though the half hour time difference between West Bengal and the border town of Phuentsholing was so inconsequential that even my usually smarter-than-me smartphone didn’t know what time to pick, pingponging back and forth between time zones during a preambular lunch with my guide and driver—my companions for the next ten days—of shamu ema datshi (yes, there’s a theme here, this time it came with mushrooms!), vegetable momos, and fried rice.

I wasn’t so much jetlagged as disoriented, with the mere hundred metre hallway separating the frenetic border town of Jaigon in India from Phuentsholing in Bhutan seemingly bridging the gap between two entirely different lands.

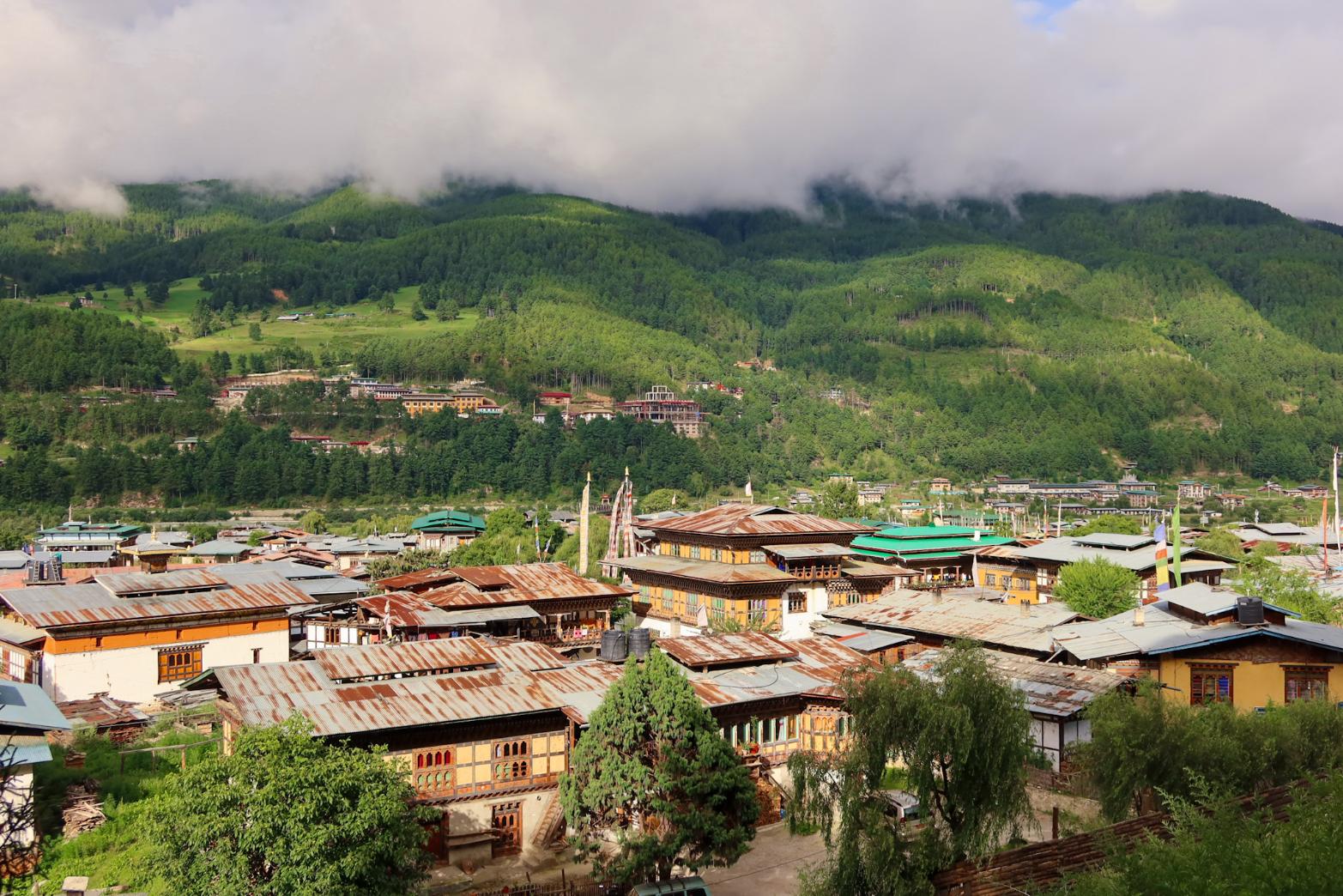

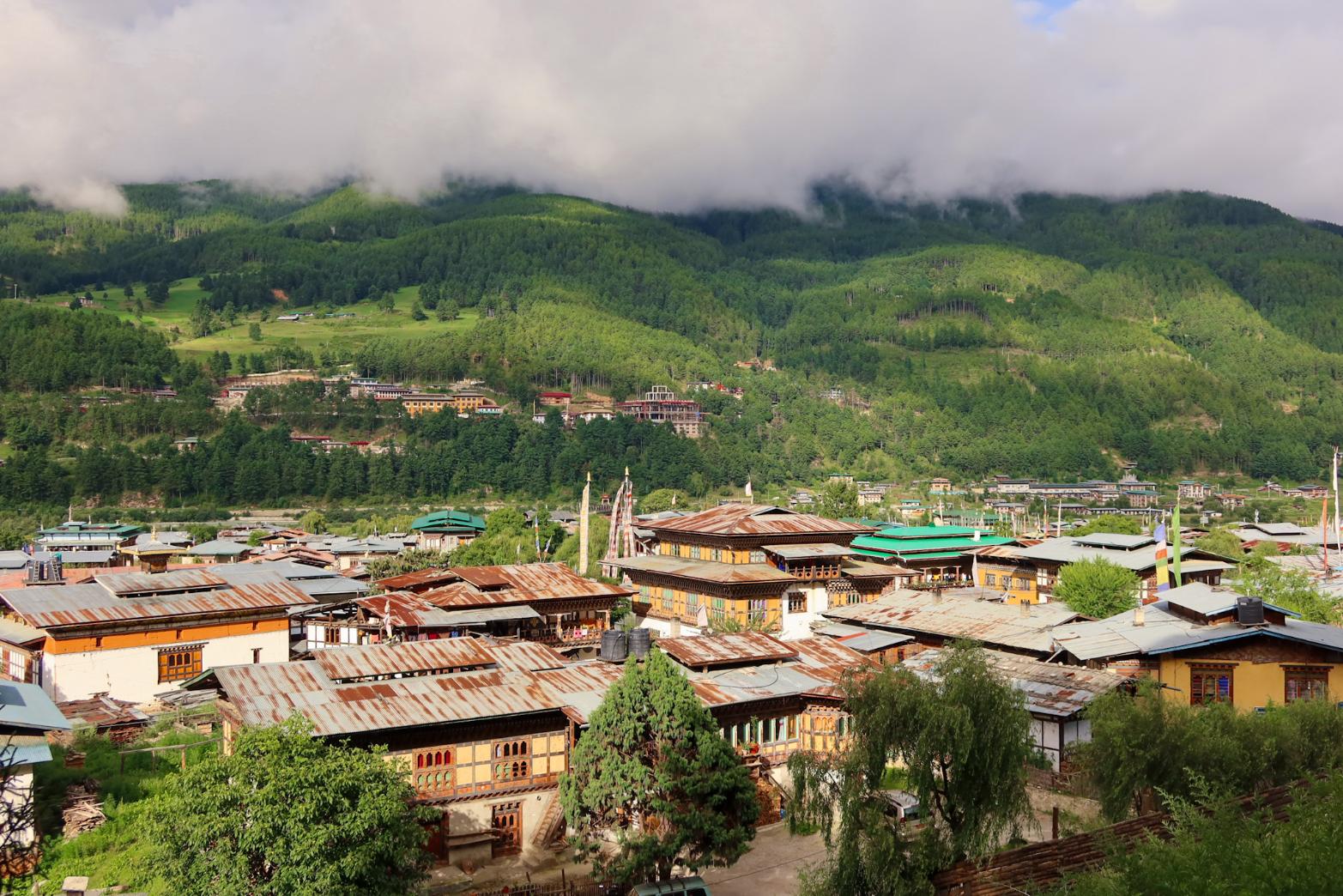

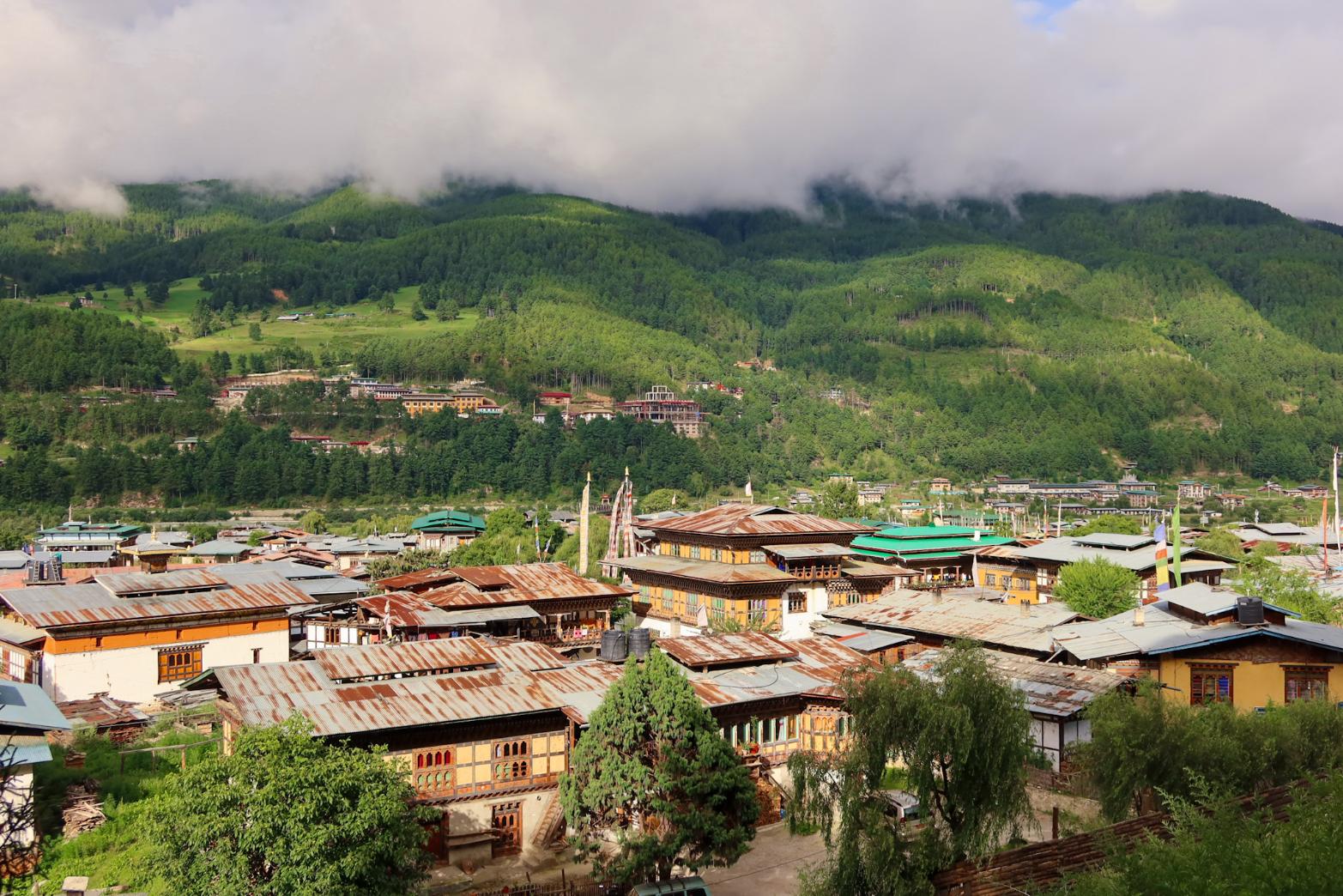

As our driver deftly weaves our red Kia through rocky couloirs and impossibly vertiginous cliff faces that look like they’re at risk of crumbling off completely—although we don’t encounter a landslide till the second last drive of my journey—it’s easy to see the Shangri-La comparisons. The aforementioned forest cover is on full display; coupled with peaks enveloped in mist, many a cow ambling onto the street with nary a care in the world, and the occasional picturesque stone or white-washed building tucked into green crevices in the hills, driving through the Himalayan kingdom feels wholly removed from the rest of the world.

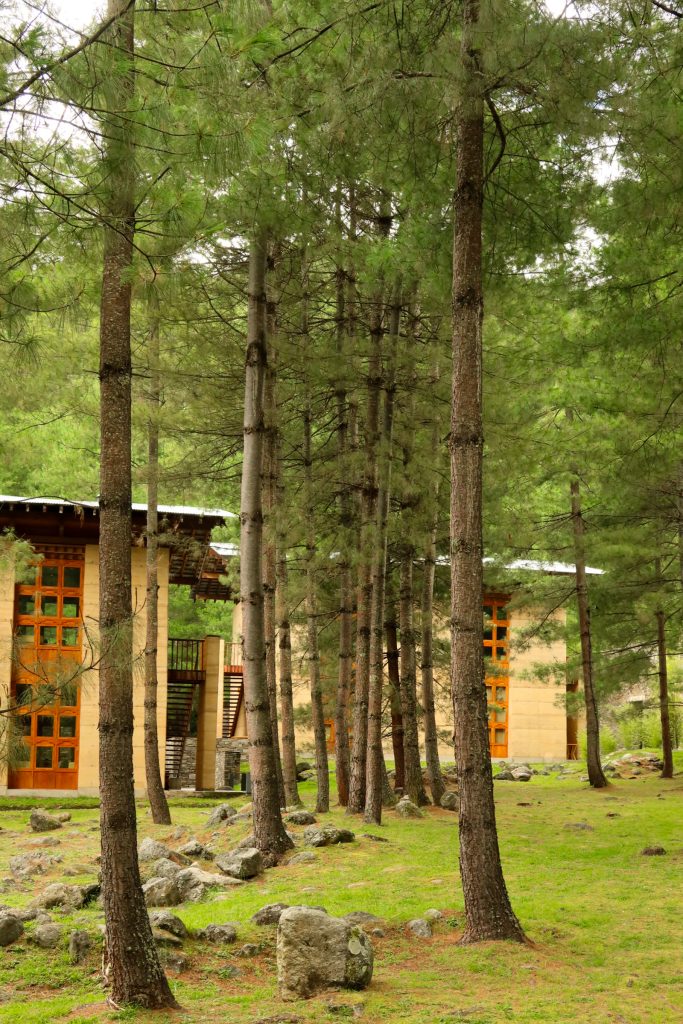

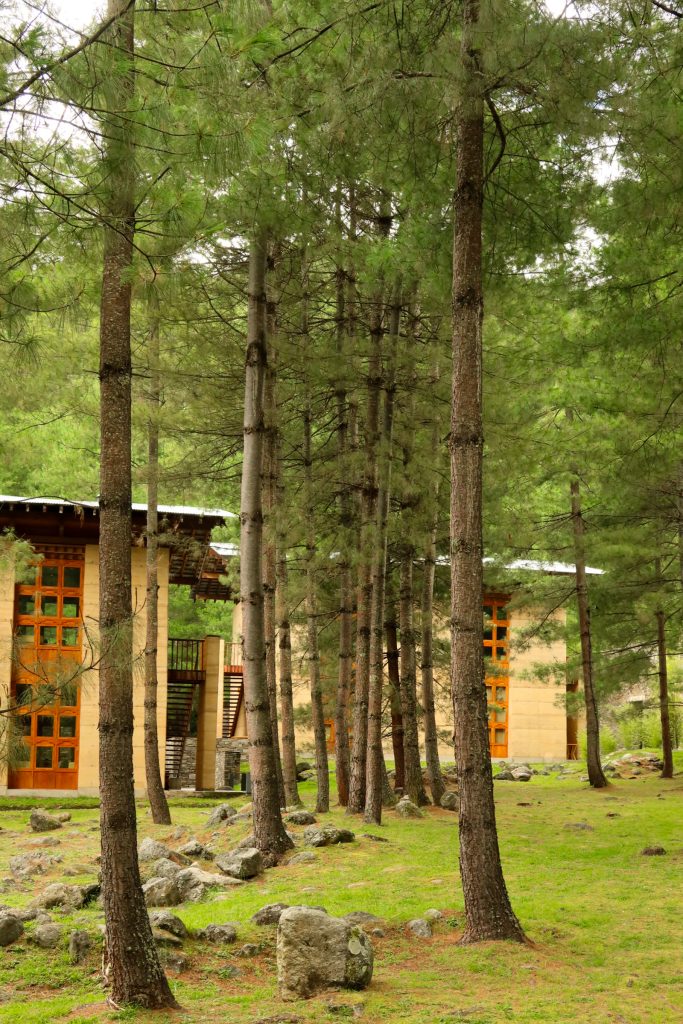

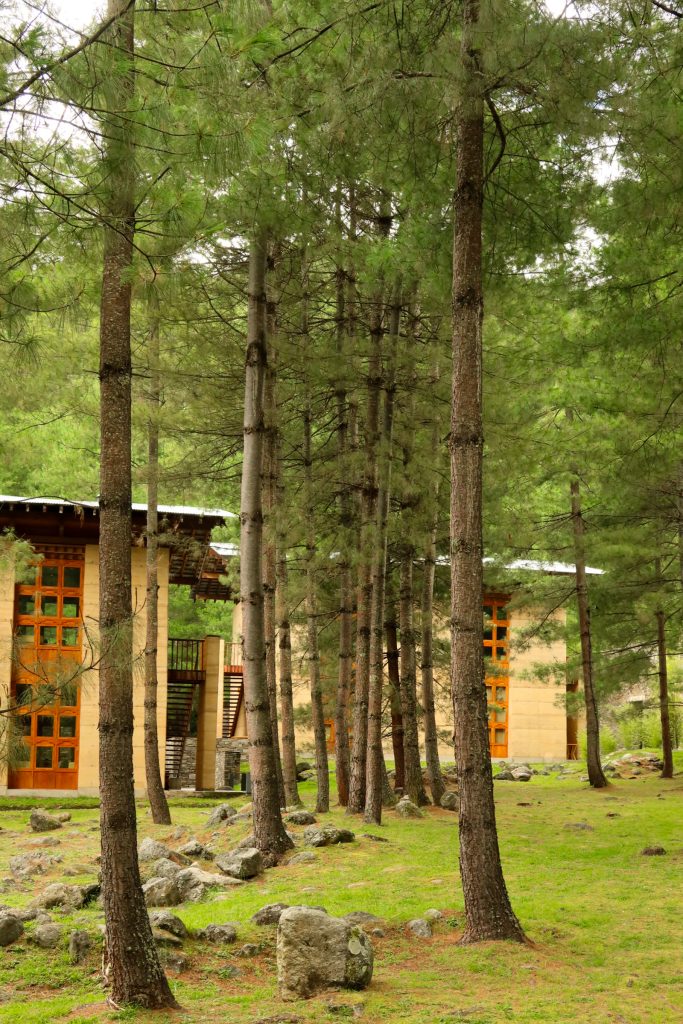

In yet another world is Amankora Paro, with the 24-suite lodge perched above the city and tucked behind a forest, the floor cushioned with so many pine needles they put a spring into the step of even the most heavy-footed traveller. Designed by late Australian architect Kerry Hill, each of the five Amankora lodges balances the prescribed vernacular of traditional Bhutanese architecture—subtly tapered walls, flying roofs, rabsels (timber frames with multiple windows), and an emphasis on locally sourced natural materials such as wood, rammed earth, and stone—with the signature essentialist design language Aman is known for. Notably, the rammed earth walls are kept free from paintings of spiritual iconography and the rabsels are devoid of carvings, resulting in a kind of monastic minimalism that turns the gaze outwards (not a difficult feat, given the communal living area overlooks the impressive Drugyel Dzong).

We wind our way east towards Punakha, cresting the Dochula Pass along the way. Sitting at an elevation of 3100 metres, the mountain pass is home to 108 memorial chortens, known as the Druk Wangyal Chortens, commissioned by the Queen Mother to commemorate the Bhutanese soldiers who lost their lives in a military operation against insurgent groups.

Descending into Punakha, the landscape changes yet again. Nestled within the valley, the former capital of the country boasts a temperate climate that supports endless terraced rice fields and even some subtropical fruits. Resting like a topaz atop the velvety green basin is Como Uma Punakha, the luxury lodge clad in golden terracotta tones that complement the verdant rice fields surrounding it. Each of Como Uma Punakha’s ten rooms and villas is oriented towards the Mo Chhu (Mother River), its tireless gushing so loud that upon entering my room I spend the first few minutes trying to figure out how to turn the air conditioning off.

At the confluence of the Mo Chhu and Pho Chhu (Father River) is the largest—and inarguably most impressive—dzong in the Himalayan kingdom. Found throughout the country, a dzong is an architectural typology which coalesces a fortress and monastery within a single entity. The vast Punakha Dzong served as the administrative hub of the nation until 1955 and is now the setting for royal coronations, many of the country’s most famous festivals and ceremonies, and the winter residence of the head of the clergy and his entourage of monks (known as the Dratshang).

Not long earlier, I was face to phallus with a head of an entirely different kind. “Would you like to make a prostration?” my guide had asked. I initially declined, not knowing what a prostration was, but linguistically associating it with other somewhat taxing or painful nouns with the -ation suffix — castration, maturation, taxation. Turns out it’s simply the act of bowing and stretching; three times in the case of tantric Buddhism, to show respect to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

The Chimi Lhakhang, a temple dedicated to Lama Kunley—known as the ‘Divine Madman’ for his unorthodox spiritual practices, which essentially amount to a rejection of celibacy and a gratuitous use of sexual innuendos—is popular with women and couples hoping to conceive, with Bhutanese and foreigners alike visiting the temple for fertility blessings.

It, like many commercial and residential buildings in Bhutan, is decorated with phalluses. Now, these are not the rudimentary two-circles-and-an-oval appendages scrawled onto chairbacks and tabletops in your average public high school classroom. No, considered symbols of good luck (the aforementioned Lama Kunley allegedly used his to banish evil spirits), they’re painstakingly rendered in great graphic detail and sometimes adorned with ribbons or bows. Later, I snap a photo of one and send my very first unsolicited dick pic.

As I knelt on the hardwood floor of the Chimi Lhakhang, looking up at a three-foot black wooden phallus, I silently prayed for its well wishes to not come my way.

“Are you alone?” a lilting voice chimes from above me. The hard midday light streams through the gilded entryway, illuminating the robed figure from behind and casting a shadow over the space. I barely have time to nod my assent, before the voice continues, “where’s your husband? Don’t you have a boyfriend? Why didn’t your friends come with you?”

“Uhh,” I gawk, displaying all the eloquence of an oversized wooden phallus and feeling rather like I did in primary school when we were asked to find a partner and I’d invariably be the one left out. “I wanted to come by myself,” I finally manage.

My shorn head inquirer breaks into a smile and sits down cross legged beside me. “That’s so cool,” she says. “I want to be independent too. That’s why I became a nun.” Over the course of about ten minutes, we have a surprisingly varied conversation about the pressure to get married and have kids, the prevalence of alcoholism and domestic violence, the struggle for financial independence, and divorce. As we sit on the floor of the Sangchhen Dorji Lhuendrup Nunnery, I’m simultaneously comforted and dismayed by the notion that for all the apparent magic and mystique, the female experience is such that sometimes, we’re all just living parallel lives in different accents.

Bhutan was one of the last nations to introduce television and internet. I know this not because of a lack of devices spotted in the country, but because it’s one of the most commonly cited statistics by publications zealously hailing the kingdom as the “last Shangri-La” and painting its traditionally garbed inhabitants as untainted by technology or external influences. But although the country may have been late to the party, the pervasive nature of the internet—and particularly social media—has meant that mobile phone addiction is a very real thing. There are red-gowned monks on TikTok and nuns on WhatsApp (“What’s up, la?” my new friend from Punakha pings me once a week). I pass schoolgirls giggling over videos of people dancing (looking rather smart in their traditional kiras as they do so) and encounter tour guides with their heads in their phones on the hike up to the Tiger’s Nest Monastery. Granted, with well over a hundred sightings of the impressive taktsang under the belts of their ghos, it’s likely just as quotidian as a walk through the CBD.

While hopes of a utopia unaffected by the influences of technology may be dashed, perhaps it’s for the best. In a way, it’s somewhat insulting to expect the kingdom and its citizens to remain frozen in time, existing as a perfect model of society for us to package up and take home; relegating them to mere supporting acts in the ‘pray’ quotient of our Eat, Pray, Love journeys.

It’s not all messages and reels though. The kingdom has been proactive in embracing technology for the sake of progress, with the last nation to introduce the internet also the first in the world to accept cryptocurrency payments for tourism-related services. Neat, huh?

And if not utopic, there’s still opportunity for the euphoric. The journey from Punakha to Gangtey takes us out of the valley and through a stomach churning climb up the mountains. As we reach the Gangteng Monastery, the sky opens up and unleashes the entire contents of its clouds onto us. Rather than yelping and running for cover as I—and a couple of other tourists—do, the robed monks seem unphased. Sure enough, a lap around the monastery later and the sun has already dried our clothes.

Ensconced in the minimalist haven of solitude that is Amankora Gangtey and sipping honeyed ginger tea, I’m gripped with a desire to be within the quaint hamlet beyond. Amankora Gangtey is the smallest of the quintet, spread across a monolithic horizontal stone structure that’s strategically oriented so that each of its eight suites captures views of the Phobjikha Valley through its three-tiered rabsels. An almost unbearably bumpy bike ride—which turned into a bike walk every time I was faced with an incline—later and I was listening to birdsong, punctuated by the occasional moo.

When it comes to describing the eastern world to those in the western world, there’s often a need to liken objects and concepts to a ‘familiar’ western equivalent to make them more accessible. “Ah, a dosa: it’s like a pancake, but Indian!” and “momos: dumplings, but Tibetan. And spicier!”

While innocuous, it’s somewhat reductive and a mild slight to one’s intelligence, as if implying that westerners are incapable of understanding things without a direct analogy. So, dear reader, I’ll refrain from insulting your intelligence by referring to Gangtey as the Switzerland of Bhutan. It wouldn’t be an inaccurate comparison though, with its rolling hills, endless greenery, wandering cows, and meandering streams flanked by lolling mountains. But, it’s a destination in its own right — one where there’s not so much to see or do, one to simply be.

A pastiche of four glacial valleys, Bumthang is both the geographic and spiritual heart of Bhutan. Known for the production of some of the country’s finest apples, buckwheat, and honey, it’s also home to some of the most auspicious temples in the country. While it may lack the architectural grandeur of the Punakha Dzong or the gravity defying awe of the Paro Taktsang, there’s a certain resonance to the simple and unassuming build of the 7th-century Jambay Lhakhang. According to legend, it was constructed in a single day, along with 107 other temples spread across Bhutan, Tibet, and the bordering Himalayas, in order to subdue a giant ogress.

The region is also home to the Kurjey Lhakhang, where Guru Rinpoche (he of flying tigress fame) is said to have subdued malevolent deities by meditating for three months, leaving behind an imprint of his body. Over a home cooked dinner at Jakar Village Lodge, my host Lucky tells me that the supernatural presence runs strong in Bumthang, with locals avoiding driving through certain sections of the road at night for fear of encountering harmful spirits with the ability to influence relationships between people and even cause illness and wounds. A family-owned and -operated business (Lucky’s mother-in-law whipped up the array of curries, vegetables, buckwheat noodles, and momos in front of me), the lodge is constructed in traditional Bhutanese style and features cosy rooms appointed with local furniture, each with a small outdoor terrace or balcony.

We also discuss the more insidious malignant spirits that have made their way into the country. Again, the matter of social media comes up, with the introduction of TikTok and Instagram having a palpable effect on the younger generation. It seems that while piety and prayer may have successfully banished ogresses and malicious deities from the land, not even three months of meditation is enough to exorcise the need to scroll.

By the time we reach the capital of Thimphu, I’m getting used to the art of simply being. The place to be? Six Senses Thimphu, a hillside luxury lodge that lives up to its moniker of a ‘Palace in the Sky’ and boasts the city’s best view of the Buddha Dordenma, the 54-metre statue of Siddhartha that watches over the capital. A short walk from the lodges is a quasi-rustic setup that sees guests find themselves in a traditional Bhutanese kitchen, complete with a bukhari wood-burning stove. It’s here that I learn to make suja, the nation’s preferred drink of slightly savoury yak butter tea (it helps if you think of it as a brothy soup, rather than a tea), and partake in the national sport of archery. Should you wish to further your journey towards enlightenment, there’s also the option to join a lama for a morning meditation session in the Prayer Pavilion. My personal brand of morning meditation involved sleeping in and watching the early risers through the floor-to-ceiling windows of the lodge’s Namkha restaurant, a cup of cordyceps green tea in hand.

Back in Sydney, a driver cuts me off in peak hour traffic. As I slam on the brakes and reach out to blast the horn, I feel the diminutive green and gold speckled wooden phallus that now dangles from my car keys brush against my thigh. I sigh and content myself by taking the middle path and simply rolling my eyes instead. I think Buddha would approve.

If there is a utopic Shangri-La, it likely isn’t anywhere that’s plottable on a map. But, for somewhere both real and really different — Bhutan is a good place to get lost looking for it.

Albert Review travelled as a guest of the Bhutan Department of Tourism, Amankora, Como Uma Bhutan, Six Senses, and Jakar Village Lodge.

Words and photographs by T. Angel